The third portion of the Loeb Jewish Portrait Database is comprised of early photographs. Although the Loeb photographs are all an early type of photo called daguerreotypes, this page is designed to give you tools to analyze the following:

Daguerreotypes

Just as silhouettes replaced miniatures, so too by the mid 1840s, daguerreotypes (“duh” + “GERR” + “uh” + “typs”) had replaced silhouettes as the cheap portrait of choice. Daguerreotypes were invented in 1839 by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre.

Like miniatures and silhouettes daguerreotypes were a “one off” form. Whereas modern photographs rely on either negatives or digital files from which multiple copies may be created, each daguerreotype was made on an individual silver plated copper while was prepared by “fuming” with iodine vapor. This plate was then placed in a camera and exposed to light. Hot mercury vapor was then used to develop the plate, followed by fixer (a hot solution of salt) and water rinses. The result was a unique image that was incredibly fragile and which was typically placed in a frame under glass (White and Barger, the Daguerreotype, 1-2).

Although some Jews were involved in the daguerreotype industry, most of the surviving daguerreotypes of Jews were made by non-Jews. The most famous Jewish daguerreotype maker was Solomon Nunes Carvalho, a Sephardic Jew originally from Baltimore. In March of 1853, Carvalho accompanied General John C. Fremont’s Fifth Expedition (1853-54) along the 38th parallel as the group’s photographer. Despite bad weather, frostbite, hunger and near death conditions, Carvalho managed to take numerous daguerreotypes of the journey with Fremont that survived his return to New York and were used to create engravings for accounts of the expedition. Unfortunately, however, nearly all the originals were lost in a warehouse fire. Only the half-plate view of the Cheyenne village at Big Timbers, taken on 20 November 1853, survived. Carvalho struggled financially to make ends meet. After his return from the West, he briefly ran a photography studio in New York.

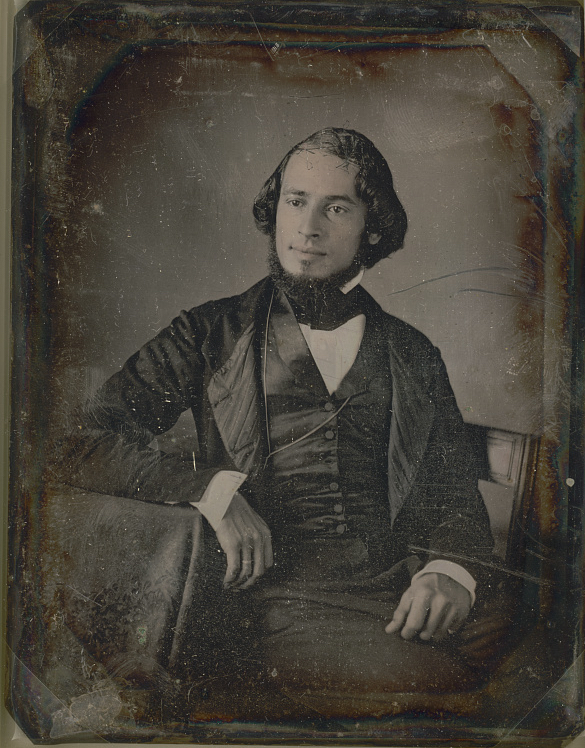

Daguerrotypes’s popularity can also been seen as connected to the rise of racial antisemitism. Unlike silhouettes which always presented the sitter facing sideways, daguerreotypes tended to present sitters facing forward or in three-quarter facial view. This was important as starting in the 1790s-1830s, Jews had became increasingly subjected to caricatures that exaggerated “semitic” features such as the nose. Moreover, part of daguerreotypes appeal was they promised to present people more truthfully. While anyone who has taken a selfie knows that photography is hardly a precise copy of the person being featured, one was to a certain extend less at the mercy of the artist’s sense of what a Jew was. The form also emphasized a quiet, sedateness. Unlike Edouart’s silhouettes which tried to capture people in the midst of a characteristic action, people had to sit quite still for daguerreotypes, which took from five to fifteen seconds to create, even in ideal circumstances (White and Barger, the Daguerreotype, 34).

Daguerreotypes remain a crucial source of information about the clothing and hairstyles of mid-nineteenth century American Jews. Unlike miniatures which often only included sitters from the chest upwards, daguerreotypes were more likely to include either the full person or a three-quarter view of their clothing (such as in Carvalho’s portrait above).

J.L. Riker, “Portrait of Johannes Ellis and his Wife Maria Louisa de Hart” (c. 1846). Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum.

One of the most interesting early American daguerreotype is from Suriname and is of Johannes Ellis and his wife Maria Louisa de Hart, whose father was parnas (president) of High German (“Ashkenazi”) Synagogue. The family’s portraits have been donated to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and consist of multiple genres of portraiture, as in addition to the daguerreotype, there is a silhouette of Maria’s father and a photograph of signed portrait of her mother.

Other daguerreotypes of Jews can be found by searching the online catalogue for the Center for Jewish History.

Cartes-de-visite and Cabinet Cards

By the 1850s, changes in photography meant that artists could produce multiple copies of photographs. Moreover, the time it took to take these photographs had decreased, allowing for more expression and versatility of what could be captured. The process required less retouching, thereby allowing photography studios to do more sittings in a day (Bachten, “Dreams of Ordinary Life,” 81). Two popular genres were cartes-de-visite (c. 1850-1910) and cabinet cards (1860s-1920s), both of which were meant for exchanging. While the Loeb Jewish Portrait Database features daguerreotypes, AJHS has many early photographs in its collection.

Cartes-de-visite were typically mounted on thicker card stock and were of a standard size: 3.5 x 4 inches. For scholars like , cartes-de-visite are about the rise of the Bourgeoise and commodity culture. In 1862, Oliver Wendell Holmes noted that “card portraits have become the social currency, the ‘green-backs’ of civilization'” (Bachten, “Dreams of Ordinary Life,” 87). Through the cards, “The person being photographed is turned into a thing, a picture, and then this thing is sold, exchanged, and consumed” (Bachten, “Dreams of Ordinary Life,” 87). However, cartes-de-visite were also a way of remembering people and keeping them close across space. As such, they were important for remembering loved ones during the civil war, but also for people separated due to immigration. If you looked at Box #2 in the Archive Interactivity, you will notice that Gertrude carried a variety of early types of photographs with her when she immigrated from Barbados. Nineteenth-century Jewish immigrants similarly often used photographs as a way of connecting to the living and dead they left behind, sometimes take family portraits next to loved one’s gravestones before they crossed the oceans. There is also a lovely collection of Jewish cartes-de-viste from Philadelphia at the University of Michigan Library. Can you identify which of the following photographs in the Moses Family Papers are cartes-de-viste?

cabinet cards were also meant for exchanging, but they were larger than cartes-de-visite: typically 4.25 x 6.5 inches. The name came from the fact that they were exactly the right size for fitting on the knick-knack filled shelves of the popular Victorian cabinets like the one shown on the right.

Like cartes de visite, cabinet cards reminded people of social obligations and helped build friendships. While cabinet cards were taken as early as the 1860s, by the 1870s they were more popular than cartes de visite. Their decline in popularity was largely due to the availability of personal cameras, which allowed families to take their own photographs.

Early Jewish Photography Studios

Art historians have noted that Jews often “took” to the new medium of photography. David Shneer speculates that this is because “Unlike many other forms of art, photography did not have an academy or jury…Its relatively low status and lack of officialdom gave aspiring young aesthetically minded Jews an opportunity to create without needing permission from those in power. It was also a new technology and a new medium, one that required entrepreneurialism and risk taking” (Shneer, Through Soviet Jewish Eyes, 15)

Wikipedia

Thus, troughout the Americas, many early photographers were of Jewish descent. In Suriname, for example, Augusta Cornelia Paulina Curiel (1873 – 1937) and her sister Anna who ran a photography studio in Paramaribo from 1904 to 1937. Like Maria Louise de Hart, the Curiel sisters were of partial Jewish, African, and Dutch ancestry. In addition to taking photos of people, she took amazing photographs of scenes in early Suriname. Collections of her photography are available online at

The Curiel sisters were not the only Jewish photographers in Suriname. Rather, several Jewish men ran studios in Paramaribo as well. Likewise Jews also ran photography studios in the early United States. In Philadelphia, for example, Cornelius Levy (?-1865) and Leon Solis-Cohen (1840-1884), ran an early studio at Ninth and Filbert Streets. Their photographs of the capital building and of the Civil War are in the collection at the Library of Congress. You can also see a gallery of their “Views of the Rebel Capital and its Environs.”

Resources

Batchen, Geoffrey. “Dreams of Ordinary Life: Cartes-de-viste and the Bourgeois Imagination.” In Photography: Theoretical Snapshots, edited by Andrea Noble, Edward Welch, and J.J. Long, 80-97. London: Taylor & Francis, 2009.

Boom, Mattie. The First Photograph from Suriname: A Portrait of the Nineteenth-century Elite in the West Indies. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2014.

Groeneveld, Anneke, Rosemarijn Hoefte, Paul Faber, and Michael Gibbs. Fotografie in Suriname 1839-1939 = Photography in Surinam 1839-1939. Amsterdam: Fragment,1990.

Hoberman, Michael. A Hundred Acres of America: The Geography of Jewish American Literary History. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2019

Noble, Andrea, Edward Welch, and J.J. Long. Photography: Theoretical Snapshots. London: Taylor & Francis, 2009.

Rivo, Steve, Carvalho’s Journey. Down Low Pictures, The National Center for Jewish Film, 2015.

Sandweiss, Martha A.. Print the Legend: Photography and the American West. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002.

Shneer, David. Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War, and the Holocaust. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011.

White, William B. and Susan M. Barger. The Daguerreotype: Nineteenth-Century Technology and Modern Science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.