In their landmark book Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century, Hazel Markus and Paula Moya argue that we should think about race and ethnicity as something we “do” rather than something we are. Here are two diagrams from Hazel Rose Markus’s slightly earlier essay, “Pride, prejudice, and ambivalence: Toward a unified theory of race and ethnicity,” American Psychologist, (2008): 651-670. Similar diagrams that are slightly more useful (for reasons explained below) are reproduced on pp. 17-18 of Doing Race, but since the illustrations below were already available on the internet, we are using them here.

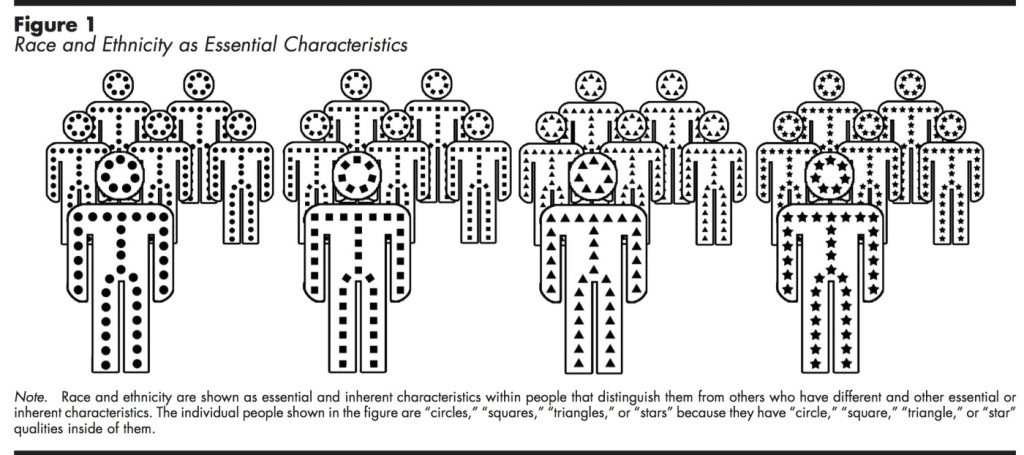

The first figure represents a common (mis)understanding of race and ethnicity as inherent or essential properties that people or groups have.

Figure 1: from Hazel Rose Markus, “Pride, prejudice, and ambivalence: Toward a unified theory of race and ethnicity.” American Psychologist, (2008): 662.

There is a slightly revised version of this figure on page 17 of Doing Race that also shows a “mixed category” person who has half stars and half triangles inside of them. This combination is useful as it suggests in this understanding of race and ethnicity, people of “mixed” races do not challenge the categories but rather become a new entity. Likewise the revised figure shows both men and women in each category. My students have noted that placing men and women within the categories is interesting, as it suggests that race and ethnicity trump gender as a category of identification.

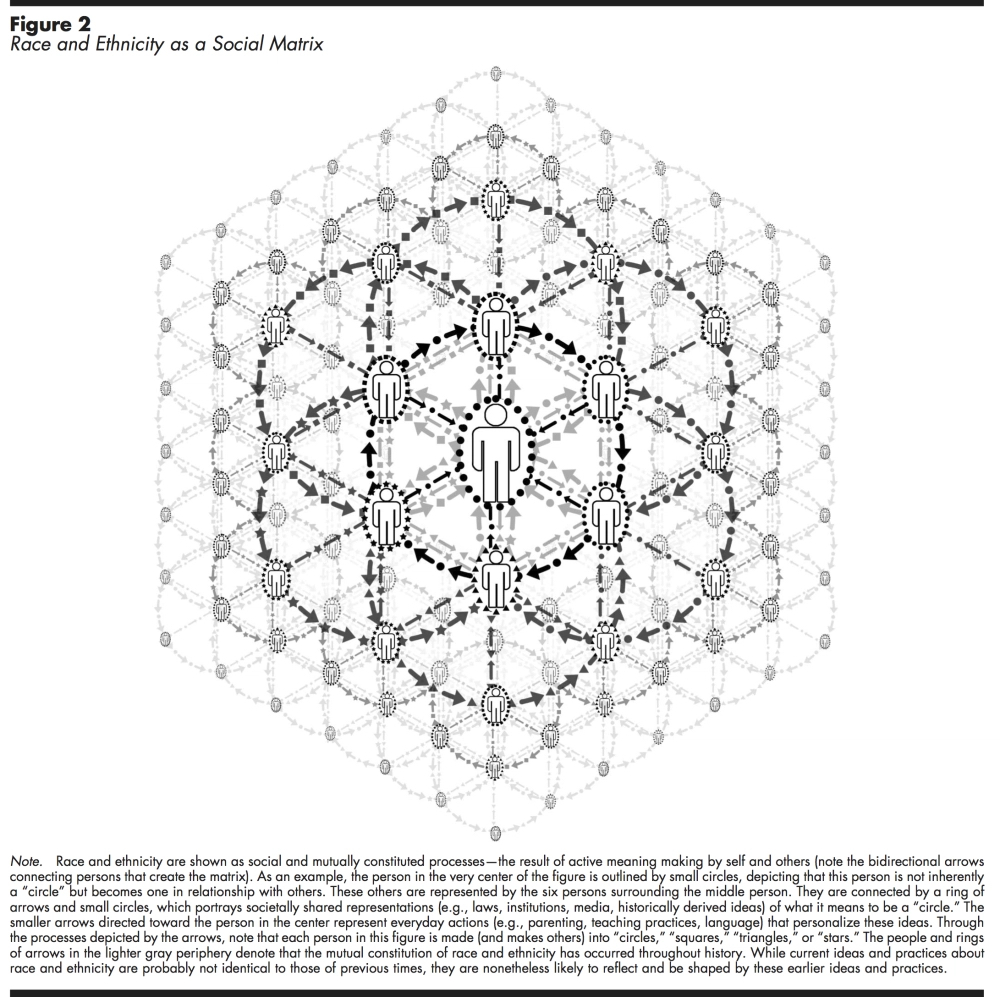

The second figure suggests a new understanding and ethnicity proposed by Markus and Moya in which race and ethnicity are something people do.

Figure 2: from Hazel Rose Markus, “Pride, prejudice, and ambivalence: Toward a unified theory of race and ethnicity.” American Psychologist, (2008): 663.

As Markus’s caption notes, in this model race and ethnicity are socially constructed processes whose meaning is made both by the self and others. Students are quick to see that understanding race and ethnicity associally constructed in part by the self gives people more agency than the first understanding of race, though does not suggest identity formation is a completely autonomous practice. Again, the revised version of this diagram from page 18 of Doing Race is somewhat more useful, in part because the figures in each circle are engaged in different activities such as dancing, running, walking, or speaking. Students often note this suggests that people might decide to identify with people across categories (e.g. dancers might identify other dancers, even though one is a star and one is a triangle). They also have noted that while Markus and Moya use these model for talking about race and ethnicity, one could also use them to talk about gender, sexuality, or other categories of identity that are sometimes essentialized.

These diagrams can be a useful way to start discussions about race and ethnicity in literary and historical texts. Often some authors we read in class don’t seem to agree with Moya and Markus’s categories (or apply these models inconsistently), the models give the students a vocabulary for talking about what is happening in the readings and what is at stake in the way the authors define race and ethnicity.

Resources:

Markus, Hazel Rose. Pride, prejudice, and ambivalence: Toward a unified theory of race and ethnicity. American Psychologist, (2008): 651-670.

Markus, Hazel Rose and Paula M. L. Moya, “Doing Race: An Introduction,” Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century, ed. Hazel Rose Markus and Paula M. L. Moya. NY: W.W. Norton, 2010.