Learning Goals

- Understand what a poem is

- Understand how Jewish American poetry has multiple roots

- Use the poetic form tool to identify the three forms used by Jewish-American poet Daniel Israel Lopez Laguna in Espejo fiel de Vidas (Life’s True Mirror, 1720)

Poetic Analysis

A number of the literary texts in both Jews Across the Americas and in the Jews Across the Americas archive are poems or songs, that is works which are broken into lines which are either written in a specific form or free verse. Jewish poetry from across the Americas draws on a wide range of poetic traditions and take their inspiration at times from Hebrew, Spanish, Ladino, Yiddish, English, and other literary schools. Likewise Jewish American poets often borrow from other ethnic American traditions, such as blues or jazz. This tutorial can help you identify what form or genre a poem is written in and provide you with resources for learning more about the associations and connotations of the form. Identifying the form is a good first step in understanding what resonances poets bring to their work.

Sample Poet – Identifying Forms

Part One of Jews Across the Americas begins with a quote from “The Exodus (August 3, 1492),” by Emma Lazarus. Lazarus describes “The Exodus” as a “little poem in prose” (that is, a prose poem), and the long lines echo the weariness of the “dusty pilgrims [who] crawl like an endless serpent along treeless plains and bleached highroads.” In contrast, some of Lazarus’s most famous poems such as “The New Colossus” and “1492” are sonnets. The sonnet form helped elevate the immigrant experience, emphasizing its centrality to the Anglo-American poetic tradition. Yet Lazarus also experimented with other forms such as the quatrains in iambic pentameter used in “In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport” that give the poem it elegiac feel.

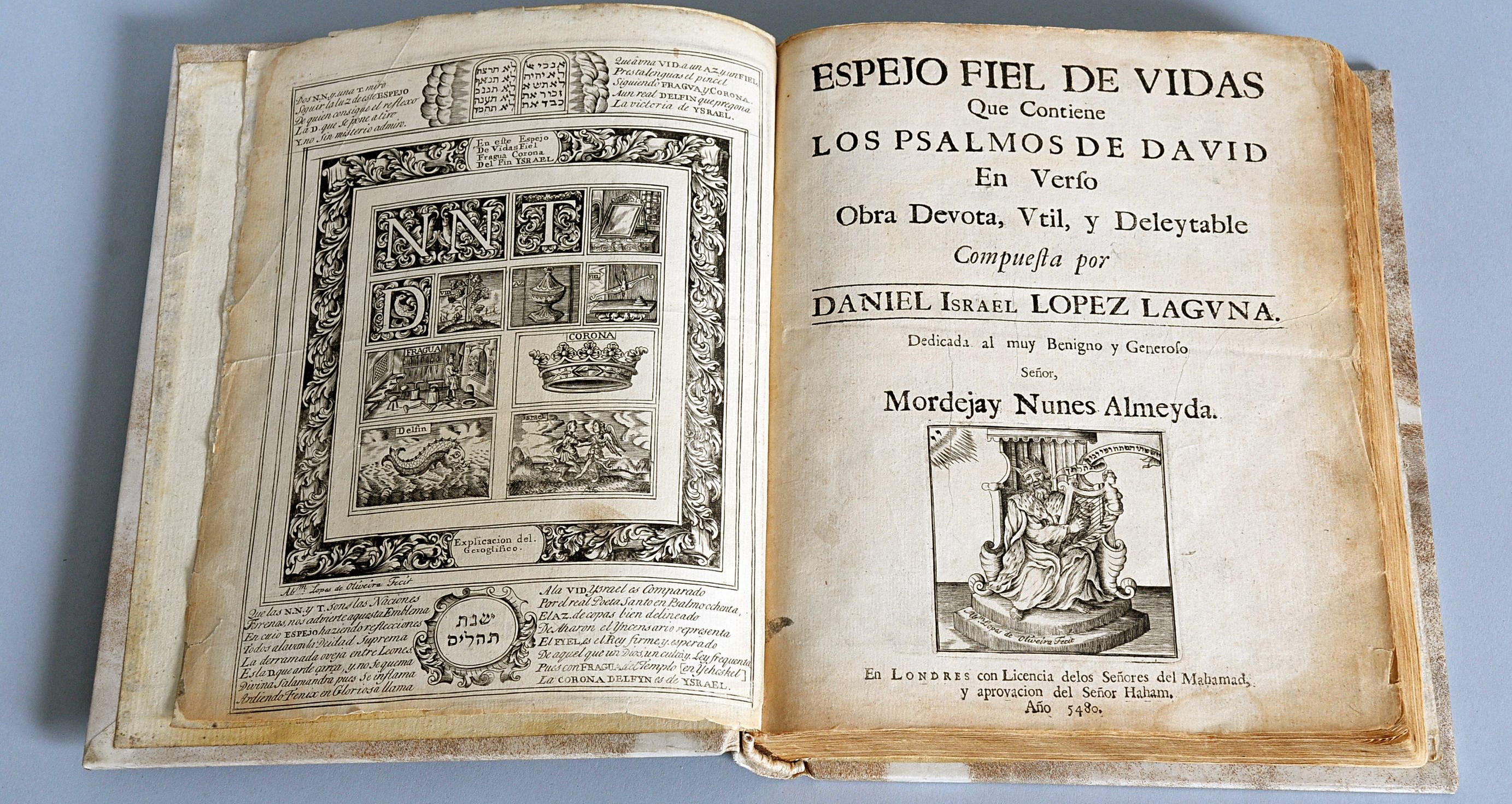

Lazarus wasn’t the first Jewish American poet to take forms seriously. An earlier Jewish American poet who reveled in poetic form was Daniel Israel Lopez Laguna. Daniel Israel Lopez Laguna composed Espejo fiel de Vidas (Life’s True Mirror, 1720) in Jamaica, though he later published the book in London. Like Lazarus, he was a Sephardic Jews, and similar to Lazarus he repeatedly carried the Jewish experience of the Inquisition into his work. A refuge of the Inquisition, Lopez Laguna was able to practice Judaism openly while in Jamaica, yet he remained haunted by what he had endured.

In Espejo fiel, Lopez Laguna translates the Hebrew psalms into Spanish. Unlike earlier translations that often used prose translations, Lopez Laguna adapts each psalm into the poetic language of Golden Age Iberia. As Laura Leibman notes, “Golden age writers took poetics seriously—particularly the ability to write in a variety of forms. Poetic academies flourished in Iberia. Poetics contests displayed publicly one’s formal training. A 1665 competition at the University of Oviedo, for example, presented awards in ten areas: ‘the first three for poetry in Latin, followed by sections for the sonnet, the canción real, the glosa, octavas, décimas, epigrams, and finally the romance‘ [Robbins 48-49]” (Leibman).

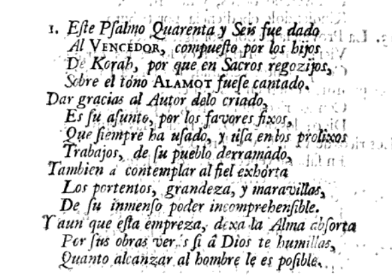

Although it won’t hurt, you don’t actually need to know Spanish to determine the form of the poems: just look to see if the end of the last word of each line rhymes with ones that precede or follow it. Three hints. 1. Ignore the numbers as those references the verses in the original Psalms. 2. the long f without a hash mark is actually an early form of “s.” 3. Lopez Laguna indicates stanza breaks either by an indentation or a space between lines. Using the poetic form finder tool below determine the form of each of the following poems, and then think about what Lopez Laguna gains by showing that he can translate Hebrew psalms in the high poetic forms valued by the Spanish Golden Age, even as his bloodline was deemed tainted by the Church.

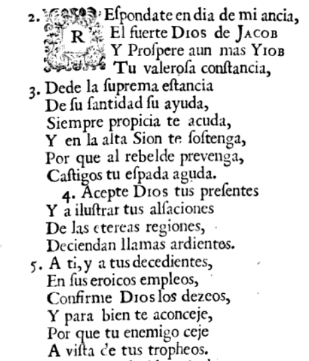

Poem 1

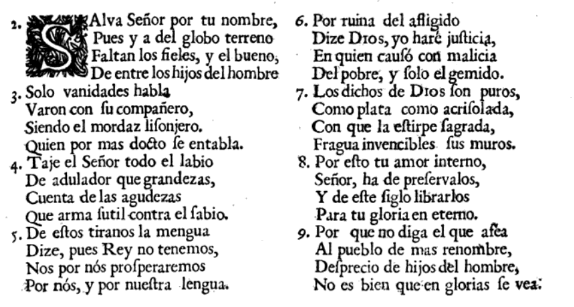

Poem 2 (only part of the poem)

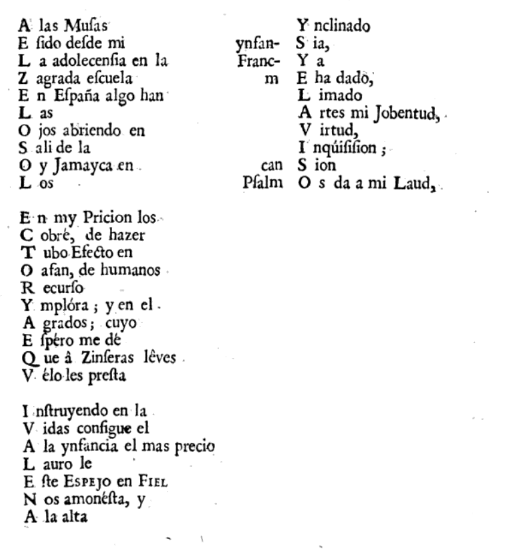

Poem 3

Poem 4